Flexible, penetrating, soaring sopranos and mezzosopranos became objects of adoration in the 18th century. According to the conventions of Italian opera at the time, they defined the pair of main characters, and when joined together, they ‘embodied the unity that the couple achieved at the opera’s conclusion and represented their idealized love.’ [2]

The most beautiful roles in 18th century Italian opera were written for these voices. The voices of castrati, adored with a veneration, expressed and symbolized masculinity, nobility, and heroism, much as tenors would in the 19th century. Without doubt, castrati held power in the theater at that time—both literally and metaphorically. They created the roles of rulers, princes, victors, and lovers, but with their sensual, powerful voices they also commanded the emotions of their audiences. Especially the first half of the 18th century can be called, without hesitation, the golden age of their art. Italian singers of this kind could be found in all the major operatic centers across Europe, from west to east, from north to south. […]

This excerpt comes from the chapter entitled The Castrato: Voice of Rome in Aneta Markuszewska’s book W cieniu korony. Muzyka w polityce Jakuba III Stuarta i jego żony Marii Klementyny Sobieskiej w Rzymie (1719–1735) [In the Shadow of the Crown. Music in the Politics of James III Stuart and His Wife Maria Clementina Sobieska in Rome (1719–1735)], published by the Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów, Warsaw 2024.

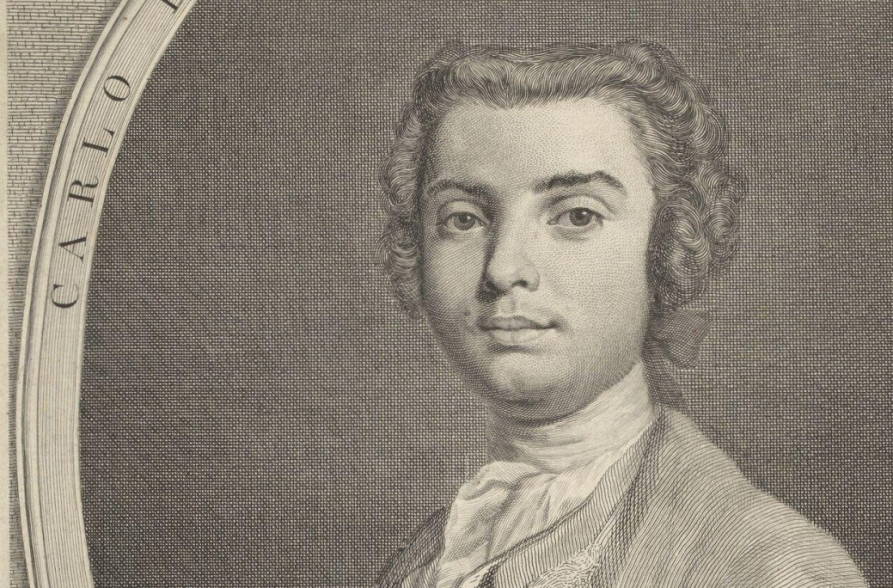

In the repertoire dedicated to the Stuarts, outstanding castrati performed. Alongside Farinelli, the operas honoring them featured the greatest castrati of the era, such as Giovanni Carestini (c. 1704–c. 1760), Gaetano Majorano known as Caffarelli (1710–1783), Gaetano Berenstadt (1687–1734), Domenico Gizzi (1687–1758), Nicola Grimaldi (1673–1732) known as Nicolini, Gaetano Fontana (1692–1739) known as Farfallino, and many others.

Footnotes

[1] Anne-Louise Germaine de Stael-Holstein, Korynna czyli Włochy, tłum. Ł. Rautenstrauchowa i K. Witte, oprac. A. Jakubiszyn-Tatarkiewiczowa, Wrocław 1962, s. 226.

[2] Naomi André, Voicing Gender. Castrati, Travesti, and the Second Woman in Early-Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera, Bloomington–Indianapolis 2006, s. 90.