Gaspard de Tende, a courtier of King Jan Kazimierz, wrote in Relation historique de la Pologne, published in 1684: ”The Poles basically do not have any breakfast or do so extremely rarely [...] In the morning, the men and the women drink warm beer soup with ginger, egg yolks and sugar”. This Frenchman, rather familiar with the land on the Vistula, was not mistaken but committed an abbreviation of sort. Writing for the French or rather the European reader he made it obvious that the Poles not break their fast in the same way as, e.g. the French.

The beer soup described by him was exactly the sort of breakfast with which many Poles of the period started their day. This once popular dish is known from recipes in old cookbooks. In a popular, universal and more humble version it was made of diluted beer with added bread or toast. Cookbooks also included a luxury version; according to a recipe from a collection made within the Radziwiłł circle in the 1680s, four egg yolks, sweet milk and a piece of butter should be mixed with the beer. According to the criteria of the period this was almost a rich repast, which should never be eaten while fasting. Such a dish was regarded as a meal and was never associated with drinking beer. The author of the recipe recommended watering down the beer if it should prove to be too strong.

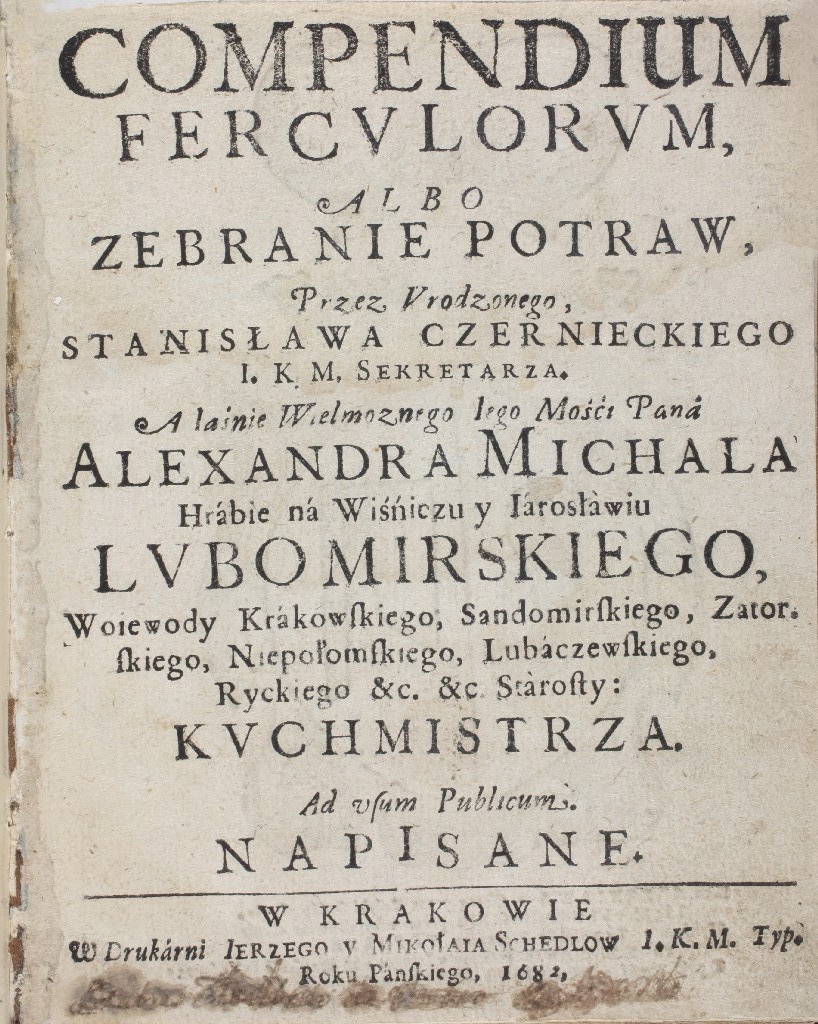

In Old Polish cuisine beer was not only a beverage, but a frequent ingredient of various dishes. To add flavour, Czerniecki recommended beer vinegar, much more popular and for obvious reasons cheaper than wine vinegar. The author of the ”Radziwiłł” cookbook permitted replacing wine vinegar with beer when the latter was of excellent quality. The author of Compendium ferculorum also advised to cook crawfish and fish à la Bohème in beer, and considered it advisable to wash sturgeon in beer before smoking the fish.

In Poland – a land of beer – this barley beverage was not only a stronger or weaker brew but also an important ingredient. It was treated as an chief element of nourishment, making it possible to avoid the use of rather inferior quality water and guaranteeing not only good flavour but also a hygienic preparation of assorted dishes.